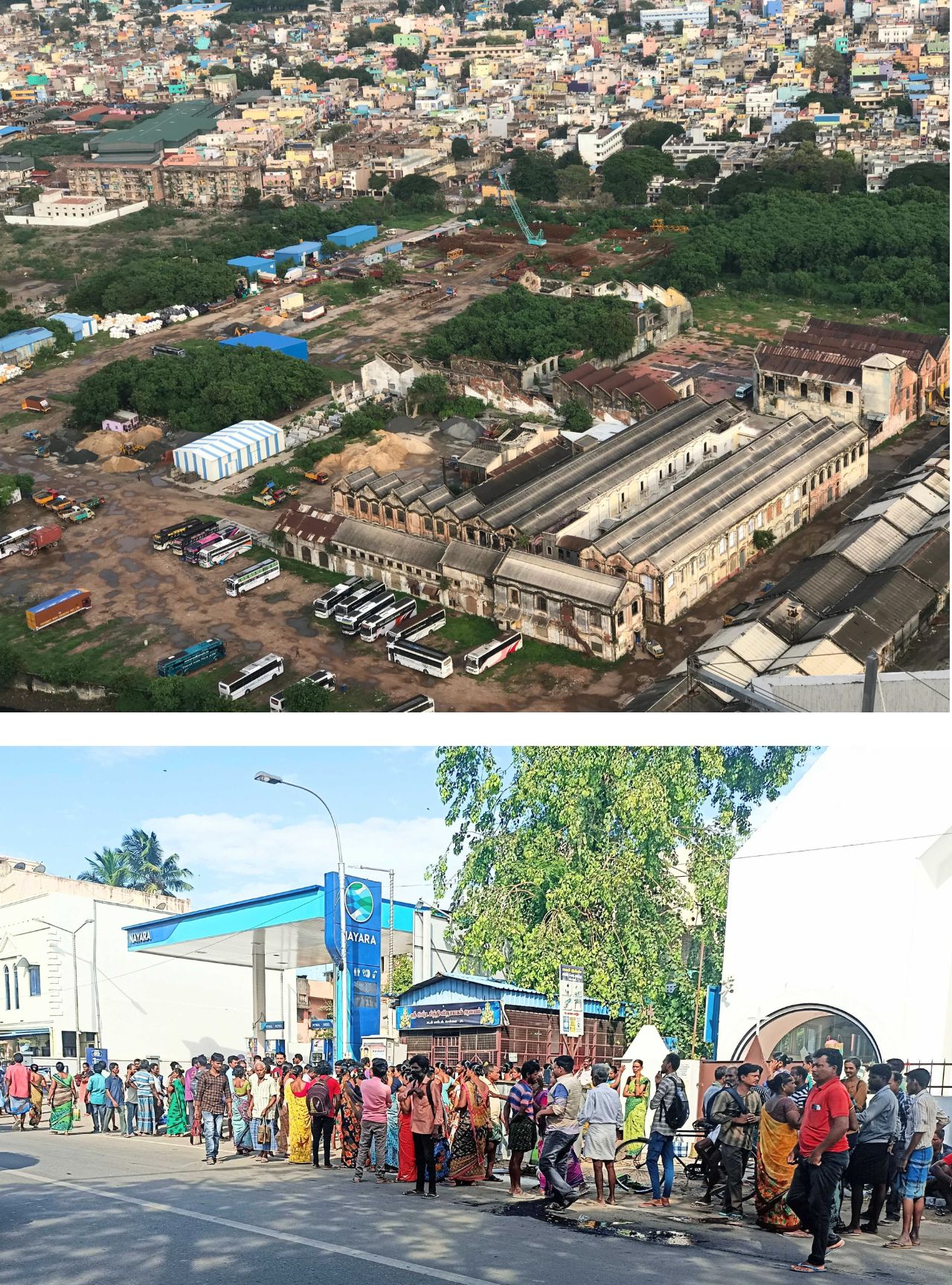

It is a story that has been retold several times. Mani, a third-generation dhobi or washerman, and his family left their village in Melmaruvathur in Tamil Nadu to settle down at the Chetpet Dhobhikana, the second oldest such facility set up by the British in the 1900s in Chennai. Mani’s son is least interested in continuing the family occupation, which is now dominated by standalone laundry outlets. There are others to take his place and work for the laundry companies. A new set of migrants, including those from UP, West Bengal and Bihar, now work and live out of this run-down facility in Chennai.

Across the city, there are many such labour hotspots – some of them new, others thriving in older industrial belts to feed the demand for cheap labour. A Cividep team, which runs a labour helpline’s Tamil Nadu chapter, found many such areas where migrants congregate in the hope of finding a job. The ‘addas’ range from defunct mill premises to small-time tea shops and entire villages. While handing over the India Labour Line helpline number 1-800-833-9020, the team found that though the job profile might have changed in some cases, issues of poor wages and insecure employment remain. Here are some stories from the spots. (Pic above: Kaliyaperumal Narayanan talks to residents of Molachur village in Sunguvarchathram about the labour helpline. They are MGNREGA scheme workers.)