Cividep India’s Study Shows That While Brands Capture Value, Workers Bear The Cost, Showing How Monopsony Power Shapes Conditions In India’s Garment Industry

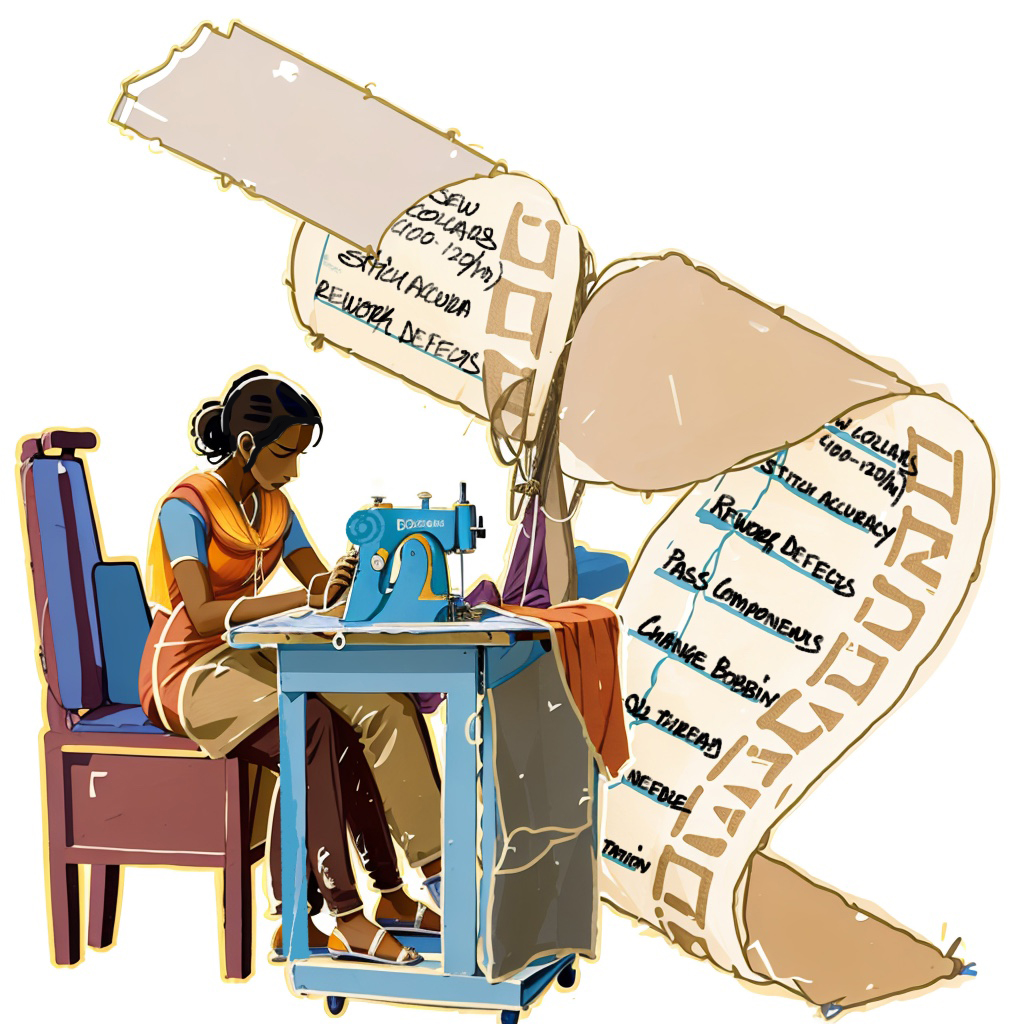

Puttathayamma has worked in Bengaluru’s readymade garment sector for over two decades, moving through 11 factories, manufacturing apparel for international fashion brands. Health problems forced her from tailoring (a semi-skilled role) to helper (an unskilled one), but the pressures persist. Overtime is compelled during peak orders, leave requests are often refused, and she frequently avoids drinking water to reduce washroom breaks. Often, overtime wage rates are not paid, as the management claims that daily production targets have not been met.

Her account is not an exception but a reflection of how global sourcing strategies shape daily life on the factory floor. Decisions on purchasing practices — how brands set prices, adjust (or fail to adjust) for wage increases, and impose lead times — are made far from these factories. These decisions determine whether workers earn enough, can take breaks, or are forced into unpaid overtime. It is precisely these structural imbalances that instruments such as the EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) seek to address. Yet whether the Directive will make an impact depends on how it engages with purchasing practices in global value chains. Its scope and enforcement architecture remain contested, as recent negotiations have seen repeated attempts to dilute liability provisions.

Reframing Brand Accountability Through The Lens of Global Monopsony

In this context, where regulatory approaches struggle to reconcile international brand power with local labour realities, Cividep India undertook a study to develop a worker-centric human rights due diligence framework. The resulting research report, Global Monopsony, Contracting Practices and Employment Outcomes: A Human Rights Due Diligence (HRDD) Framework for Garment GVCs, documents how monopsony power, exercised through strategic sourcing choices by international fashion brands, cascades down to the shop floors of garment factories in the Global South.

One of the fundamental questions that the study explores is whether brands can be held responsible for working conditions in supplier factories given that brands do not directly employ these workers. It argues that since manufacturers produce apparel under contracts that follow brand specifications, the brand-supplier relationship should be viewed as one of ‘contracted production’ rather than a simple buyer–seller arrangement.

Brand-supplier relations are thus re-examined through the lens of monopsony capitalism — a market situation where a handful of buyers in the Global North (fashion brands) exert undue control over numerous manufacturers in the Global South. Crucially, the study contends that monopsony is not a natural market outcome but a strategic choice. Using monopsony power, the brands (or lead firms) set not only technical requirements but also the prices and supply conditions that manufacturers must accept or risk losing business.

Reimagining HRDD: Addressing Brand Practices and Human Rights Risks

To examine this premise, the study assessed two critical spheres of the garment value chain:

1) brand-manufacturer relationships (contracting practices)

2) employment outcomes (human and labour rights risks)

These are key points of action for any HRDD measures or processes adopted by brands and manufacturers. In order to make the process outcome-oriented rather than merely a compliance exercise, the study devised an HRDD framework with operational definitions for the main areas of risks identified within these two spheres. Based on this, it sets indicators and benchmarks to measure progress and have concrete outcomes, using a method similar to the Global Indicator Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

This framework was then tested through field surveys across three major garment manufacturing clusters in India — Bengaluru, Delhi NCR, and Tiruppur — to assess the prevalence and severity of labour rights risks. For assessing contracting practices, interviews were conducted with 27 garment manufacturers across the three production clusters. Data on employment outcomes were gathered through a survey of 607 workers in Tier-1 export-oriented garment factories.

Key findings:

Squeezed margins and shrinking lead times: Manufacturers reported that lead times for fulfilling orders have fallen from an average of 112 days five years ago to just 79 days. Nearly 70% said brands do not adjust prices when technical specifications change, while all calculated labour costs on the basis of minimum and not living wages.

Persistent wage and rights deficits: Worker surveys revealed a disconcerting 30 per cent wage gap between actual wage received by workers and the legal minimum wage, and a 72 per cent gap when compared to the estimated living wage. Moreover, only 40% of those who work overtime are compensated at the legally mandated overtime rate. More than half reported prevalence of verbal or physical abuse at their workplaces.

The full report provides the detailed set of findings under each area of risk, set against their corresponding indicators and benchmarks.

Allocating Costs and Responsibilities

While the study does not prove direct causation, it identifies clear patterns connecting brand purchasing practices with adverse working conditions:

Wage suppression: By keeping contract prices fixed even when wage rates rise, brands prevent manufacturers from paying workers beyond — or sometimes even up to — the legal minimum.

Extractive labour practices: Sudden order changes and compressed lead times allow manufacturers to enforce excessive overtime, raise production targets, and use gender-based harassment as a managerial tool to control workers.

Precarious employment: Order volatility and price rigidity often allows manufacturers to hire short-term contract workers.

These dynamics raise a crucial question: who bears the cost of mitigating such human rights risks? Under monopsony, most of the benefits of low labour and environmental costs accrue to lead firms, as compared to manufacturers. By exploiting competition among manufacturers, brands capture much of the gains of reduced costs.

The study therefore recommends “common but differentiated responsibility” between brands and manufactures to mitigate and prevent human rights risks across the value chain. Some of these include:

1. Living wages as the baseline: Brands and retailers must finance living wages as part of standard labour costs.

2. Re-costing environmental services: Brands and consumer markets should share the costs of cleaner production (effluent treatment, energy transition) in proportion to their consumption.

3. Improving workplace outcomes: Manufacturers must address job insecurity, gendered forms of control and abusive supervision by committing to labour regulations , supported by brands through longer lead times and stable order commitments.

4. Institutionalising dialogue: Manufacturers should create a conducive environment for freedom of association and collective bargaining at the workplace to enable legitimate worker representation, as well as strengthen statutory worker committees.

This approach aligns accountability with power, ensuring that those who capture value also bear the cost of ensuring decent work.

Situating HRDD Framework Amidst Emerging Regulations

What would dignity at work mean for Puttathayamma? It would mean drinking water when thirsty, taking leave without fear, earning a wage sufficient for her family’s needs, and being paid legally mandated dues for legitimate overtime work. These are not aspirational luxuries but basic rights.

By situating workplace violations within the structure of monopsony capitalism, the study spotlights the systemic processes that perpetuate poor labour conditions. Based on this, it has proposed a five-step HRDD framework, which draws from international standards, including the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains in the Garment and Footwear Sector.

However the study goes beyond outlining HRDD as a five-step process. Its distinct contribution lies in developing concrete indicators and benchmarks that shift HRDD from a procedural exercise to an outcome-oriented tool. These metrics are grounded in a baseline assessment of human rights risks and can help stakeholders set clear goals, monitor progress, and evaluate whether business practices are improving conditions for workers. In this way, the HRDD framework provides trade unions, civil society groups, manufacturers, and brands with a practical approach for assessing risks and measuring improvements.

The framework also recognises that accountability extends beyond brands and suppliers. States play a critical role in enforcing labour standards, and in ensuring that competition for global orders does not drive them to weaken regulations in a ‘race to the bottom’.

It complements emerging global regulations such as the CSDDD as well as India’s National Guidelines on Responsible Business Conduct (NGRBC).