Workers’ Voice

Workers’ Voice brings you the true stories of garment workers, highlighting the challenges they face every day. Through reports and infographics, we showcase their struggles with wages, working conditions, discrimination, and other human rights risks within global supply chains. Explore the realities of their lives and share their stories.

Wage Sufficiency

Wage sufficiency means earning enough to meet essential needs like food, clothing, housing, and medical care, while also ensuring security against unemployment and unexpected expenses. A Cividep report reveals that only 1% of garment workers earn even half of what’s considered a living wage, with just 3% making more than the industry minimum. This illustrates the gap between gross and living wages in cities like Bengaluru. Nearly 58% of workers in Cividep’s latest report (Home & The World of Work) identified higher wages as their top priority, citing inadequate earnings that force them into overtime or additional jobs. Take a look at the infographic below to understand the challenges faced by many garment workers just to get by.

The True Cost of Low Wages

Garment worker Sheela’s monthly challenges involve juggling multiple jobs and cutting back on essential expenses like nutritious food and medical care. To make ends meet, she often skips meat and fruits, walks instead of taking the bus, and goes without hygiene products or medicines. She saves ₹500 by avoiding doctor consultations and another ₹500 by forgoing entertainment and outings. Her efforts reveal the reality of financial instability and inadequate healthcare, impacting both her and her children’s future.

Worker Story

Have You Seen This Harried Woman Who Races Past Busy Traffic Signals Off Mysuru Road? Meet Sheela, A Tailor at A Big Garment Factory, Whose Low Pay Doesn’t Leave Much For Having Healthy Meals or Comfortable Work Commutes

It’s The Long Way Home Everyday For Sheela

By Sandhya Soman & Sharmada Kaushik

Till recently, Sheela (name changed) would zip through the bylanes of Jawaregowdana Doddi on foot to reach her office on the busy Mysuru Road. With its glass and concrete façade, the garment factory could be mistaken for an IT company, another Bengaluru staple that attracts young talent nationwide.

However, the comparison ends there. Despite recent layoffs, the typical software job still offers competitive salaries and perks, a far cry from Manju’s monthly earnings of Rs. 10,500 – barely half of what’s considered a decent living wage. Her daily hour-long morning walk has nothing to do with fitness but all to ensure that she punches in on time at the factory without ‘wasting’ a single rupee on bus fare. In the evening, after an exhausting 8-hour tailoring shift, the 35-year-old single parent retraces her steps home to her mother and son.

“Susth aadru maadbekalla (Don’t I still have to do it even if I’m tired?),” asks Sheela matter-of-factly. She now occasionally takes the bus to work, thanks to the Karnataka government’s free travel scheme for women. Her composure slips when discussing her son. “Sometimes I think I could have provided him with a better education if I earned more,” she says, her eyes welling up with emotion.

Money Matters

Her meager wage is at the heart of Sheela’s struggle despite years in the industry. Starting with Rs. 5,500 in 2010, her monthly income now is a mere Rs. 9,500 post-deductions. Meanwhile, her monthly expenses have soared to Rs. 11,500 (see graphic). Her mother, earning Rs. 6,000 as a housekeeper, can only contribute minimally to the household finances.

Sheela’s plight is not unique. India’s garment manufacturing industry, with an annual turnover of thousands of crores, employs millions of workers, with a significant majority being women. In Bengaluru alone, over 1,500 units employ nearly 5 lakh women, many earning below Rs. 10,000, as per the latest Cividep report (link).

The prevalence of low wages among workers, particularly affecting women and migrants, is largely attributed to the dominance* (link) of major global brands wielding considerable monopoly power. These brands engage numerous Indian suppliers to gain a competitive edge, forcing suppliers into cut-throat competition. They, in turn, pass the burden onto their workforce through high workload demands and low wages.

The state’s long-overdue initiative towards adopting a living wage by 2025 signifies a crucial step towards rectifying this disparity and moving towards a more sustainable labour environment.

A Frugal Strategy

For now, the consequence is wages that fall far short of what’s necessary for a decent standard of living, as defined by the ILO. Sheela’s family diet lacks meat or fruits, relying solely on basic provisions from the state’s public distribution system. Their modest one-bedroom dwelling in Rajarajeswari Nagar sees few indulgences, with eating out and gift-giving reserved for special occasions.

Sheela often works overtime to supplement her income, earning extra to cover rent, school fees, and groceries. However, unexpected medical emergencies wreak havoc on her budget, compelling her to seek additional income through tailoring work for neighbours – 4-5 sari blouses to make Rs. 2,000 more.

Family Debts

Sheela’s family background is similar to several garment workers, who are first-generation factory employees (report link). In 2003, at age 15, Sheela dropped out of school due to financial pressures and moved from rural Mandya to Bengaluru with her family. Her father and elder brother worked as a security guard and a driver, respectively. Upon marriage at 17, Sheela faced financial constraints as her husband controlled her income. “He (husband) used to control what I did and didn’t give much money. He also drank a lot,” recalls Sheela.

Four years later, his death left her with the responsibility of raising their son and repaying loans for her father’s medical bills and her husband’s dialysis treatment. Sheela took up a garment factory job, but it took her five years and briefly working for the creditors to repay most of the debts. Sheela has been back at her factory job for the past two years. Her mother continues to repay a Rs. 4 lakh loan for her father’s medical expenses.

Emotional Toll

Life is far from steady as every month there would be some emergency. The stress levels are so high that the mother keeps a close watch on her daughter. “Nam ammange bhaya (my mother is scared),” she says. So much so that Manju has no social interaction apart from routine transactional conversations with colleagues and neighbours. Conversations about her personal life, especially her dreams for her son, overwhelm her at multiple points, possibly pointing to the need for an emotional outlet.

In Cividep’s latest report, nearly 58% of garment workers surveyed said higher wages were their top priority. The reason? Insufficient earnings, cited by 88% of respondents. To make ends meet, 82% of workers resorted to overtime, while 16% took on additional jobs, spending an extra two hours a day working outside the factory. (*link). This highlights the urgent need for living wages.

ILO notes that millions of workers worldwide cannot afford healthy food, decent housing, medical care, or schooling for their children due to low wages. In this context, the Indian government’s plan to introduce living wages by 2025 is crucial to improving workers’ livelihoods.

Sheela has no option but to be frugal. On some days, exhaustion kicks in, and she pauses. Then she remembers her son’s dream to join the police force. “Nam jeewna hengo nadidhoythu; aadre nam maga vodli antha ashte kashta padtairadu (My life will run somehow but I’m working hard so that my son doesn’t have to live like me).” She hopes to save more for his future.. “Maybe, I will save some money this month and I can put him in a better school,” she says, breaking into a rare smile.

Discrimination

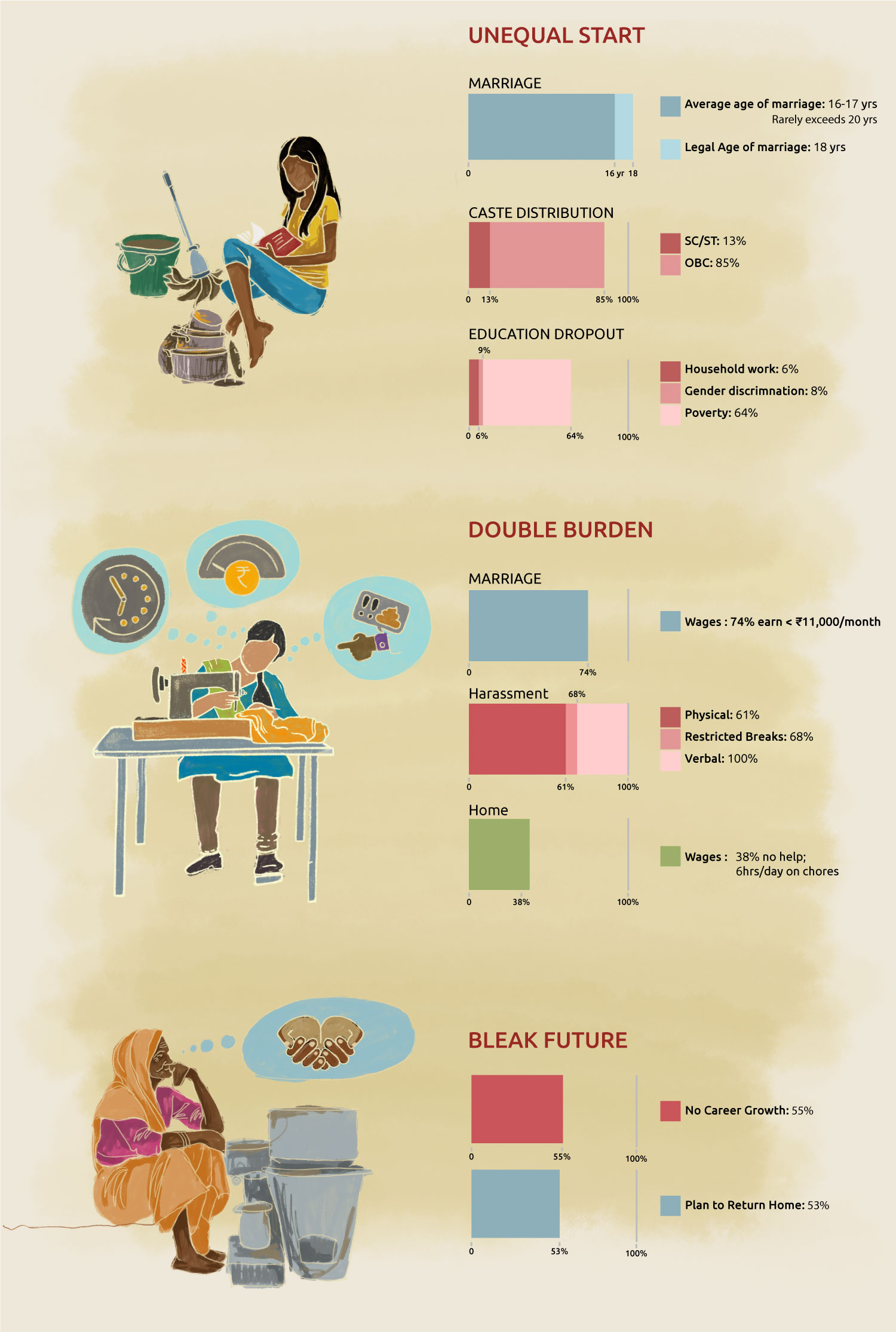

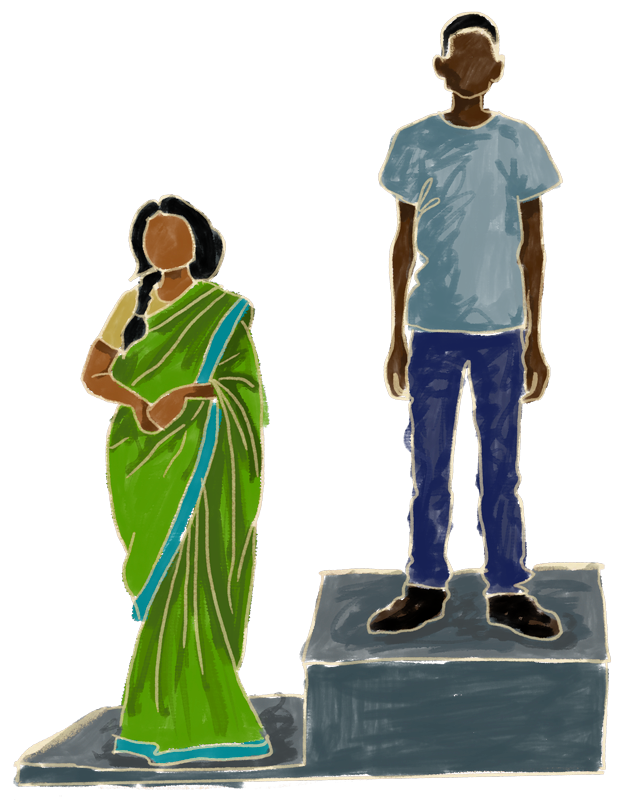

Gender discrimination remains a widespread issue, resulting in unequal pay, limited opportunities, and heavier workloads for women. Despite international agreements like the UN Human Rights Declaration and CEDAW, women in global value chains, particularly in the garment sector, continue to face deep-rooted inequities. In India, gender bias begins early, with families prioritising boys’ education while women shoulder the burden of unpaid domestic work. This inequity carries into low-wage industries like garment manufacturing, where women often experience exploitation and financial insecurity. Cividep’s latest study (link) shows that by age 40, many women are physically and emotionally drained from years of underpayment and discrimination. The graphic below highlights this journey — from childhood struggles to workplace exploitation and financial instability in later life.

The Life Cycle of a Garment Worker

From childhood, women like Lakshmi face inequality shaped by caste and poverty. Growing up in a lower-caste household, education takes a backseat to household chores. By 17, she is married, and school is a distant dream. As a garment worker, Lakshmi earns less than ₹11,000 monthly, faces harassment, and juggles factory and home duties with little help. As retirement nears, with no savings or career growth, Lakshmi faces an uncertain future. Like many, she plans to return to her village, trapped in a cycle of discrimination and struggle — an all-too-common story for several garment workers.

Worker Story

Saroja Fought Hard To Break Into Garment Work. But After Three Decades of Stitching The Same Seams, She’s In The Same Spot, Choosing Friendship Over Advancement and Survival Over Ambition. Now, She Pours Her Hopes Into Her Granddaughter’s Future.

She Broke Into Tailoring, But Stayed Stuck For 30 Years

By Nikita Joseph

Can you imagine training yourself for a promotion during lunch breaks? Learning how to operate an industrial sewing machine on a near-empty stomach with the help of a few seniors? Saroja (name changed) did a career pivot in the 1990s, long before it became an HR trend. This high school dropout went from being a helper, who scooped up textile bits in a huge garment factory, to a tailor.

This was a successful pivot in an industry that doesn’t offer growth opportunities for its largely female workforce. “I did not know that I could call myself a tailor. When I applied for jobs at other factories, I said that I could stitch sleeves or collars,” recalls Saroja, a 55-year-old resident of Bengaluru, with a smile. She got the jobs but her growth story seems to halt there. In the last three decades, Saroja has remained a tailor despite shifting to more than 10 workplaces for better salaries, and less abusive work environments. Contrast this with the career trajectory of Saroja’s junior colleague and friend Palani, who got opportunities to upskill, and rise to managerial roles with better pay.

Systemic Biases Prevalent

The stagnant position isn’t due to a lack of potential or drive – the odds against a female worker are one too many. “Women rarely go beyond the role of supervisor,” says Saroja. But talented men can go on to become general managers. The disparity also shows up in unequal pay for male and female supervisors, says Saroja.

But why then did Saroja refuse a supervisory role when offered one in 2009? At that point, she was at the forefront of a collective demand for a long overdue wage increment at her factory. The women persisted even in the face of termination threats. Finally, when Saroja and her colleagues threatened to stop work, the officials assured them an increment.

Her leadership among the factory’s workforce did not go unnoticed – the General Manager was quick to ask her to be a supervisor. She and fellow workers knew this was a ploy – it was easier to get her terminated from the new position citing her inability to get workers to meet their targets. She turned down the offer. “I wouldn’t have been able to support my fellow workers if I took up the role,” she says.

United They Don’t Stand

Times have changed since then. “There used to be unity among workers but now this is not the case,” says Saroja. This is perhaps why she doesn’t make much of the rising number of female supervisors appointed by her current employer. “Increasingly, the management has started forcing workers to stay back till as late as 1 am to complete targets. The male supervisors couldn’t bear such pressure and resigned,” says Saroja.

Getting female tailors and helpers to replace them was the obvious choice – they are more pliable and could also be expected to pitch in with the work. Saroja considers the new female supervisors to be pro-management.

When asked how these changes have affected the dynamics among the workers, Saroja says: “They have no regard for friendships; their only aim is to get the others to complete production targets.” She is resigned to how management tactics distort and dismantle the possibilities of female leadership. Her experiences also make her doubt her abilities. “I am uneducated and weak in English; so I might not be able to do the record-keeping and documentation work required of a supervisor,” she says.

She does not make much of her life’s work – one spent single-handedly raising a family, persisting through abusive and dead-end jobs, and growing to be a recognised union leader. “Girls these days do not aspire to work in the garment industry, and rightfully so. They are looking for better opportunities.” This observation also links to the evidence pointing to high attrition rates among women workers in the garment industry. ‘The Home and The World of Work’ report shows that the majority of the local workers surveyed (98%) were in the peak years of their working lives. However, 53% had spent just between one to five years in these factories, and there was a clear decline thereafter. Only 30% had spent 6-10 years, and just 10% had spent 11-15 years working in the industry.

As for Palani, Saroja has only good wishes for him. When Palani got promoted, she was one of the persons he had called. “My blessings will always be with you,” she told her friend. Her confident and engaging demeanour falters only when speaking of her family. “I am content with whatever I’ve got so far. My only regret is not being able to educate my daughter better.” Saroja hopes to make up for this by educating her granddaughter and helping realise her dreams.

Extractive Labour Practices

Extractive Labour Practices refer to the exploitation of workers through excessive, unpaid labour under duress. Defined by the ILO, forced labour includes any work imposed on individuals under threat, without their voluntary consent. Rightful working conditions are a far cry for garment factory workers in India, who toil long hours to meet unrealistic production targets set by high-street brands, enforced by their Indian suppliers. Cividep’s latest study reveals that 94% of Bengaluru’s garment workers endure grueling 9-hour shifts, often extending to 12 hours, with no respite in terms of pay or leave (see below infographic).

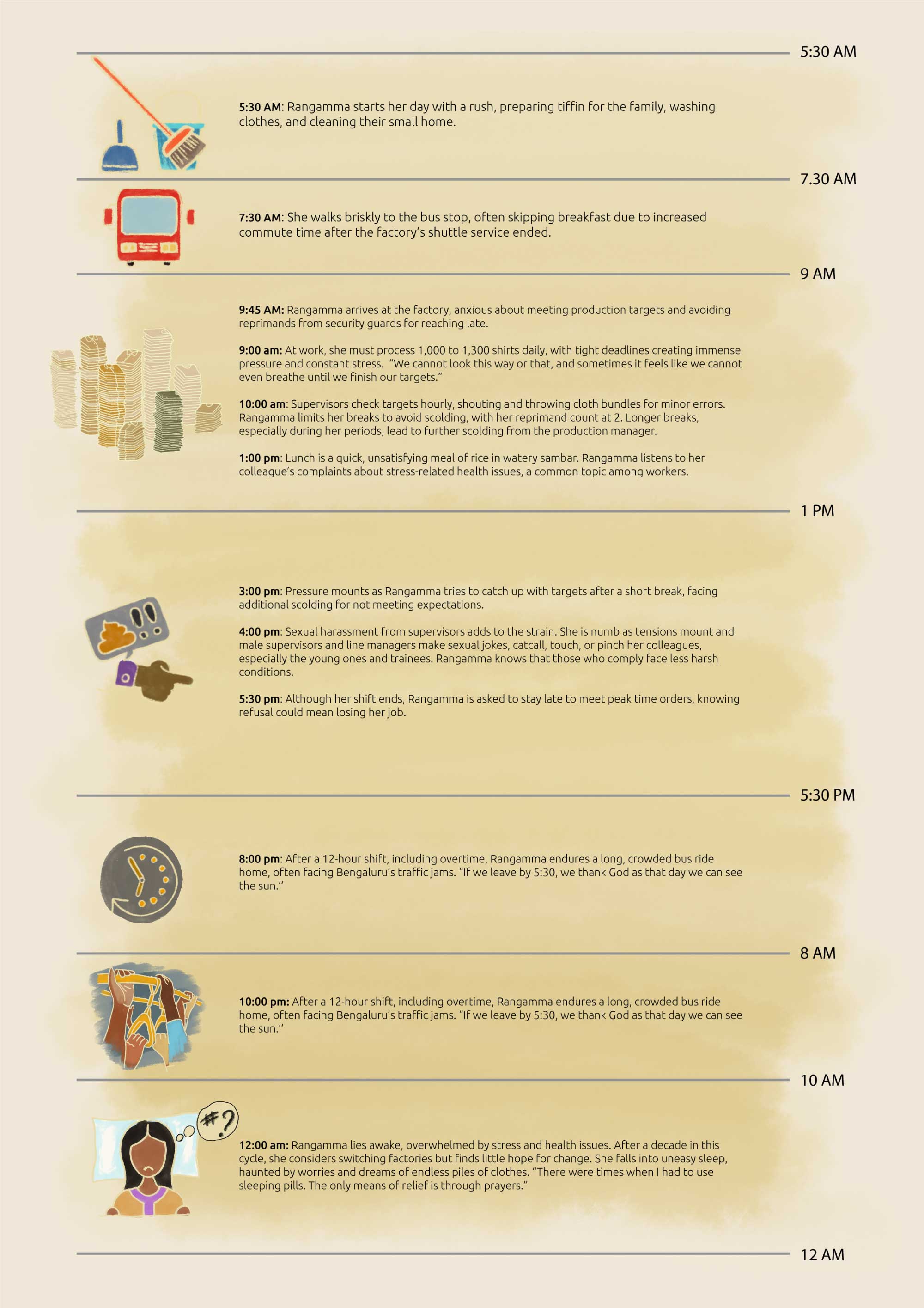

A Day in the Life of Rangamma

Workers like Rangamma, who stitches shirt collars for high-end brands in a Bengaluru export factory, endure relentless pressure and abuse to meet impossible demands. Starting her day at 5:30 am, she faces verbal, physical, and sexual harassment throughout her shift. This graphic illustrates Rangamma’s exhausting routine, from early morning to midnight, highlighting the stress and exploitation she and her fellow workers experience. This systemic abuse has profound social and personal consequences.

Worker Story

Work Shouldn’t Be Torture. But When Yelling, Shouting & Physical Abuse Are Normalised at Garment Factories That Chase Targets, Workers Like Seetha Remain In Perpetual Fight-and-flight Mode

Desperately Seeking Respect

By Nikita Joseph

Three months into her first job as a tailor at a Bengaluru garment factory, 20-year-old Seetha (*name changed) had had enough. A small error she had made incited her supervisor to yell and throw a bundle of cloth at her, even as her colleagues watched. She tried her best to stay on but she only lasted another three months, before she resigned in the hope of finding a better workplace.

This was in 2007. More than 15 years on, the 36-year-old has concluded that her work environment is not going to change, no matter how many job hops she does. Seetha appeared for the interview tired, wary, and afraid of losing her job for talking about her experiences at four different factories in a decade.

“It is torture,” is how Seetha described her work environment. From skipping lunches and toilet breaks to staying mum through coercion and abuse from supervisors, she has seen it all, so her employers can meet unrealistic production targets that seem to be increasing every other year.

Why Is Work ‘Torture’?

Seetha’s is not an isolated experience. The Home And The World of Work report cites how in its survey of 184 Bengaluru garment workers , 100% and 61% of the local workers (those hailing from Karnataka) reported experiencing verbal and physical abuse (having a bundle of clothes thrown or a chair pushed at them) respectively. As many as 68% of the workers said that their factory imposed time restrictions on the use of the toilet, and these are enforced by controlling the number of visits and amount of time spent in the toilet, as well as through verbal abuse. Nearly 66% experienced physical isolation inflicted as a form of punishment and 39% had undergone sexual harassment.

These methods are imposed due to short lead times (time given by brands to contract manufacturers to deliver orders). There is intense pressure on shopfloors to complete work, and supervisors pass on the burden to workers through verbal, physical, and sometimes sexual abuse, and penalties. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) refers to these extractive labour practices as situations in which persons are coerced to work through the use of violence or intimidation (Read more).

Garment factories have been using such practices despite interventions and international outcry. Many of them have devised novel ways to extract more from their employees. At Seetha’s second workplace, the dining room was strategically placed four floors above the shopfloor so workers would rather miss lunch and not ‘waste’ time using the stairs. “The days I managed to drink water once a day were memorable,” she recalls.

The other tactic from the same employer was to force workers to do overtime (OT) regularly and give them a day off instead of the mandatory OT pay. This is illegal as workers should be paid double their wage rate for overtime work. Seetha says she prefers to earn more because the regular wage is low.

No Break

When such work practices lead to physical ill-health, the workers find it humiliating to avail of sick leave. “If you’re here just for time pass, you might as well sit at home,” says the supervisor when workers go with leave requests. Permission is a long-drawn-out process – approvals have to come from the supervisor, floor-in-charge, Production Manager, HR, and sometimes, General Manager. Complaints lead to more work and penalties.

Such practices have been normalised in the garment industry over the years. Among the respondents for the Home And The World Of Work (link) research study, about 82% of the local workers said that they did overtime work, while only 58% of them were paid double for overtime work. In addition, about 70% of the workers said that they are asked to work on Sundays or other public holidays, but 58% of them are given what is known as a compensatory off sometime during the week, instead of the legally mandated overtime pay.

At a point in her five-year tenure as a helper at factory number two, Seetha was fed up with being hauled up by her supervisor for every small ‘mistake’. In response, she garnered the strength to take an unexpected step. Once she countered her supervisor: “I’m doing my best to complete the work on time by not even eating lunch. If you can do what you are asking me to, I’ll admit that I’m at fault.” Such a response only elicited more retribution.

When things went beyond control, she reported her supervisor to Munnade Social Organisation, a Bengaluru-based non-profit dedicated to the welfare of women garment workers. The Production Manager was brought in and upon checking Seetha’s machine, he accepted that she was right. He dismissed the supervisor and took her back to work.

New Ways Of Control

Small victories like this remain exceptions, as strategies to systematise a culture of coercion continue. After the pandemic lockdowns, work pressures have intensified. The factory started appointing more female supervisors, touted under the garb of female empowerment. “Female supervisors can harass us more as they even follow us to the washrooms and lunch hall,” says Seetha. “They come inside the washrooms and accuse us of taking breaks.”

Seetha has witnessed how many former friends and peers have changed after being promoted to supervisors. “They don’t have the permission to remain friends and if they talk to some workers differently, they will be termed partial,” she says.

Seetha may not be surprised by these everyday betrayals, but she is not resigned to her fate. During the lockdowns, she engaged in piece-rate work from home for another factory, which did not pay two months’ dues. Seetha decided to change her factory and is now at a marginally better workplace. Here, the latest by which workers can enter the gates is 9:15 am, after which they have to report late coming, whereas, in factory number 2, the gates were shut by 9:05 am. She is also paid the legal rate for overtime work now. Her current role, which involves stitching collars, does not come under a target-based system. These are only small changes, but Seetha feels much more relaxed about work than before.

Salaries across all factories remain abysmally low and hardly rise beyond Rs. 9,500 per month. Seetha has chronic back pain, headache, joint pain, and anaemia. She is the sole breadwinner of her family, as her husband has stopped economically supporting them. The one time her face lights up is when talking about her son, whom she has admitted into a computer science course at a private college. She dreams of a bright future for him, where he is respected at his workplace and free from abuse. And perhaps then, she can finally let go of a career that has taken much more than what it has given her.