Workers’ Voice

Workers’ Voice brings you the true stories of garment workers, highlighting the challenges they face every day. Through reports and infographics, we showcase their struggles with wages, working conditions, discrimination, and other human rights risks within global supply chains. Explore the realities of their lives and share their stories.

Discrimination

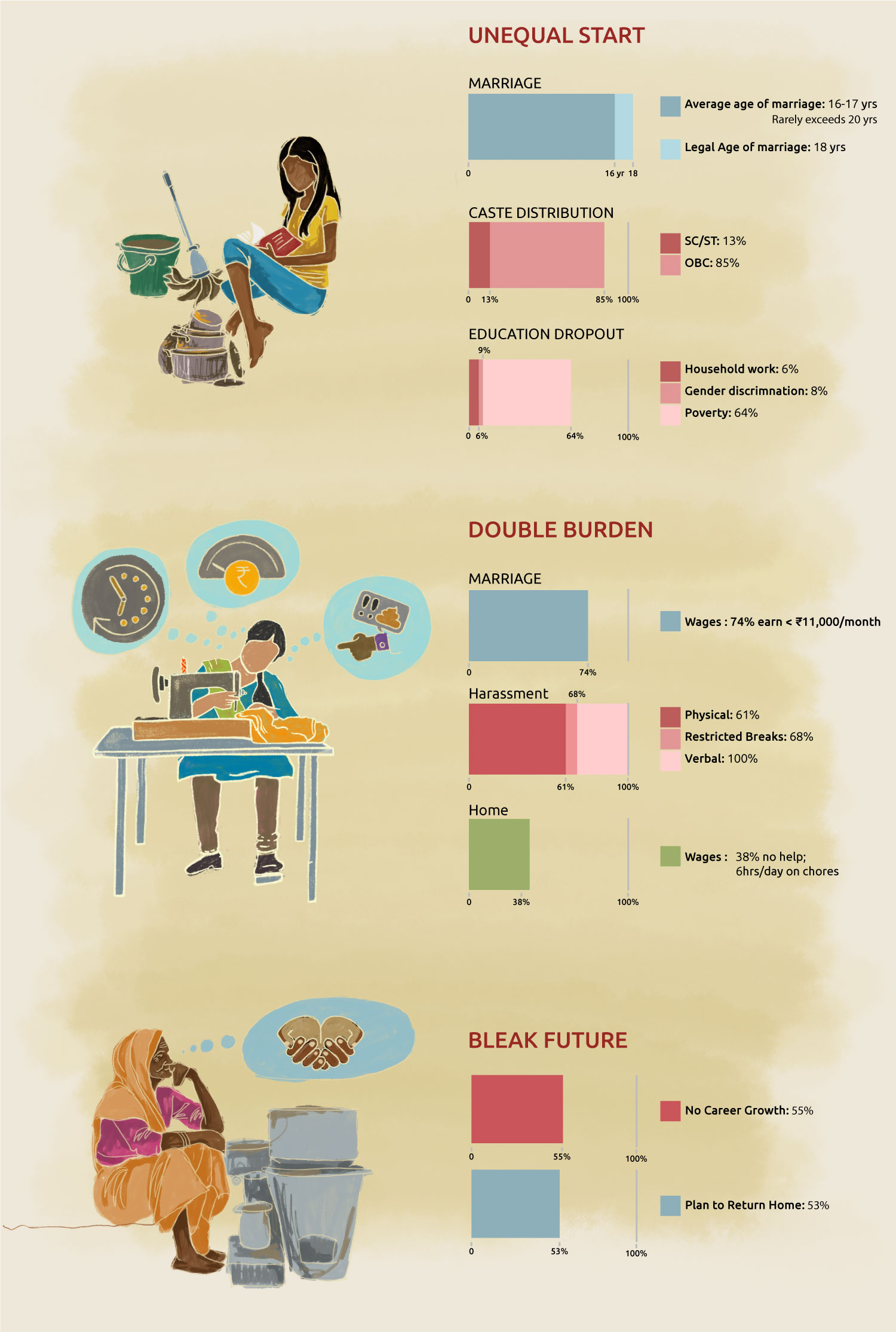

Gender discrimination remains a widespread issue, resulting in unequal pay, limited opportunities, and heavier workloads for women. Despite international agreements like the UN Human Rights Declaration and CEDAW, women in global value chains, particularly in the garment sector, continue to face deep-rooted inequities. In India, gender bias begins early, with families prioritising boys’ education while women shoulder the burden of unpaid domestic work. This inequity carries into low-wage industries like garment manufacturing, where women often experience exploitation and financial insecurity. Cividep’s latest study (link) shows that by age 40, many women are physically and emotionally drained from years of underpayment and discrimination. The graphic below highlights this journey — from childhood struggles to workplace exploitation and financial instability in later life.

The Life Cycle of a Garment Worker

From childhood, women like Lakshmi face inequality shaped by caste and poverty. Growing up in a lower-caste household, education takes a backseat to household chores. By 17, she is married, and school is a distant dream. As a garment worker, Lakshmi earns less than ₹11,000 monthly, faces harassment, and juggles factory and home duties with little help. As retirement nears, with no savings or career growth, Lakshmi faces an uncertain future. Like many, she plans to return to her village, trapped in a cycle of discrimination and struggle — an all-too-common story for several garment workers.

Worker Story

Saroja Fought Hard To Break Into Garment Work. But After Three Decades of Stitching The Same Seams, She’s In The Same Spot, Choosing Friendship Over Advancement and Survival Over Ambition. Now, She Pours Her Hopes Into Her Granddaughter’s Future.

She Broke Into Tailoring, But Stayed Stuck For 30 Years

By Nikita Joseph

Can you imagine training yourself for a promotion during lunch breaks? Learning how to operate an industrial sewing machine on a near-empty stomach with the help of a few seniors? Saroja (name changed) did a career pivot in the 1990s, long before it became an HR trend. This high school dropout went from being a helper, who scooped up textile bits in a huge garment factory, to a tailor.

This was a successful pivot in an industry that doesn’t offer growth opportunities for its largely female workforce. “I did not know that I could call myself a tailor. When I applied for jobs at other factories, I said that I could stitch sleeves or collars,” recalls Saroja, a 55-year-old resident of Bengaluru, with a smile. She got the jobs but her growth story seems to halt there. In the last three decades, Saroja has remained a tailor despite shifting to more than 10 workplaces for better salaries, and less abusive work environments. Contrast this with the career trajectory of Saroja’s junior colleague and friend Palani, who got opportunities to upskill, and rise to managerial roles with better pay.

Systemic Biases Prevalent

The stagnant position isn’t due to a lack of potential or drive – the odds against a female worker are one too many. “Women rarely go beyond the role of supervisor,” says Saroja. But talented men can go on to become general managers. The disparity also shows up in unequal pay for male and female supervisors, says Saroja.

But why then did Saroja refuse a supervisory role when offered one in 2009? At that point, she was at the forefront of a collective demand for a long overdue wage increment at her factory. The women persisted even in the face of termination threats. Finally, when Saroja and her colleagues threatened to stop work, the officials assured them an increment.

Her leadership among the factory’s workforce did not go unnoticed – the General Manager was quick to ask her to be a supervisor. She and fellow workers knew this was a ploy – it was easier to get her terminated from the new position citing her inability to get workers to meet their targets. She turned down the offer. “I wouldn’t have been able to support my fellow workers if I took up the role,” she says.

United They Don’t Stand

Times have changed since then. “There used to be unity among workers but now this is not the case,” says Saroja. This is perhaps why she doesn’t make much of the rising number of female supervisors appointed by her current employer. “Increasingly, the management has started forcing workers to stay back till as late as 1 am to complete targets. The male supervisors couldn’t bear such pressure and resigned,” says Saroja.

Getting female tailors and helpers to replace them was the obvious choice – they are more pliable and could also be expected to pitch in with the work. Saroja considers the new female supervisors to be pro-management.

When asked how these changes have affected the dynamics among the workers, Saroja says: “They have no regard for friendships; their only aim is to get the others to complete production targets.” She is resigned to how management tactics distort and dismantle the possibilities of female leadership. Her experiences also make her doubt her abilities. “I am uneducated and weak in English; so I might not be able to do the record-keeping and documentation work required of a supervisor,” she says.

She does not make much of her life’s work – one spent single-handedly raising a family, persisting through abusive and dead-end jobs, and growing to be a recognised union leader. “Girls these days do not aspire to work in the garment industry, and rightfully so. They are looking for better opportunities.” This observation also links to the evidence pointing to high attrition rates among women workers in the garment industry. ‘The Home and The World of Work’ report shows that the majority of the local workers surveyed (98%) were in the peak years of their working lives. However, 53% had spent just between one to five years in these factories, and there was a clear decline thereafter. Only 30% had spent 6-10 years, and just 10% had spent 11-15 years working in the industry.

As for Palani, Saroja has only good wishes for him. When Palani got promoted, she was one of the persons he had called. “My blessings will always be with you,” she told her friend. Her confident and engaging demeanour falters only when speaking of her family. “I am content with whatever I’ve got so far. My only regret is not being able to educate my daughter better.” Saroja hopes to make up for this by educating her granddaughter and helping realise her dreams.