Workers’ Voice

Workers’ Voice brings you the true stories of garment workers, highlighting the challenges they face every day. Through reports and infographics, we showcase their struggles with wages, working conditions, discrimination, and other human rights risks within global supply chains. Explore the realities of their lives and share their stories.

Extractive Labour Practices

Extractive Labour Practices refer to the exploitation of workers through excessive, unpaid labour under duress. Defined by the ILO, forced labour includes any work imposed on individuals under threat, without their voluntary consent. Rightful working conditions are a far cry for garment factory workers in India, who toil long hours to meet unrealistic production targets set by high-street brands, enforced by their Indian suppliers. Cividep’s latest study reveals that 94% of Bengaluru’s garment workers endure grueling 9-hour shifts, often extending to 12 hours, with no respite in terms of pay or leave (see below infographic).

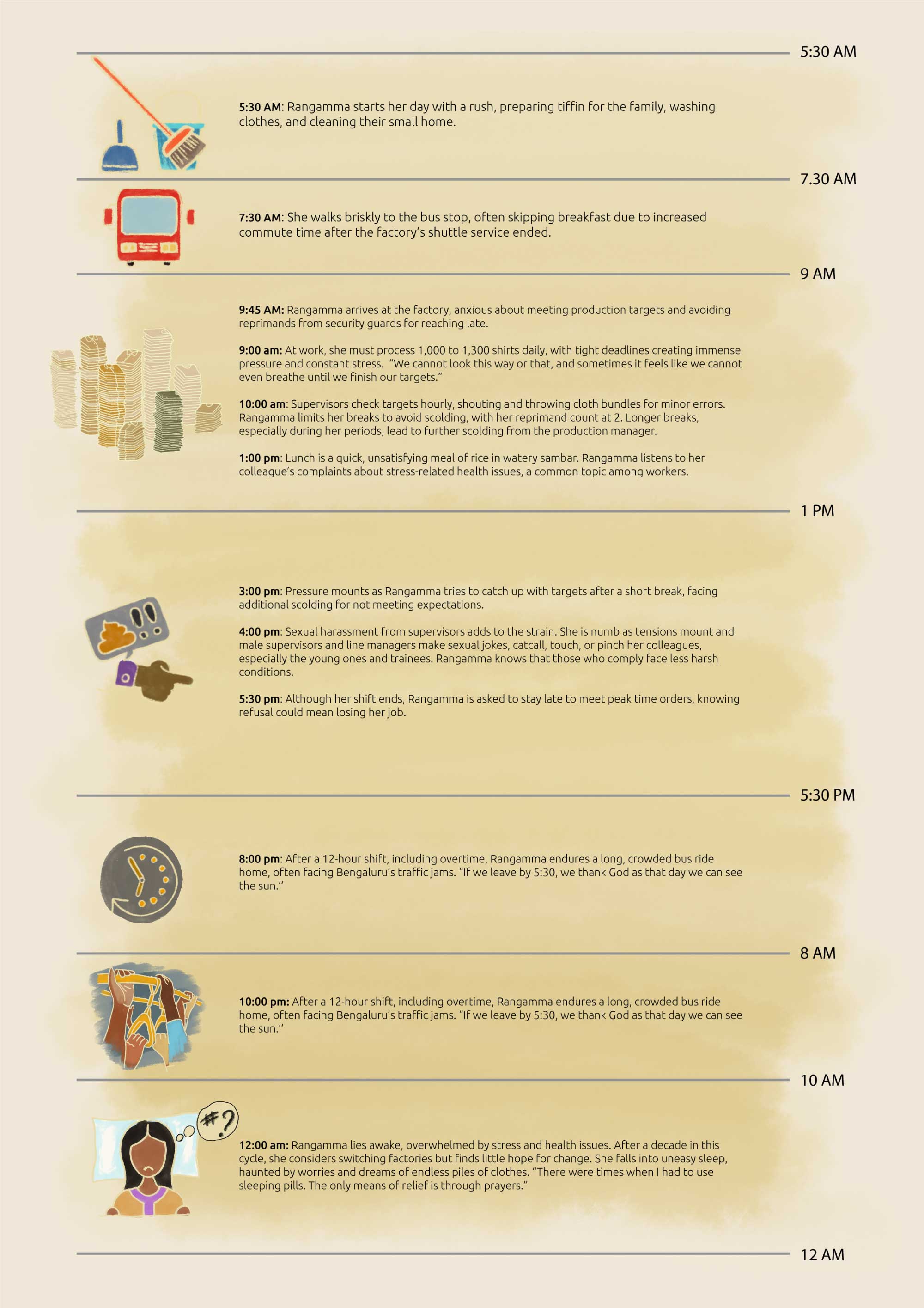

A Day in the Life of Rangamma

Workers like Rangamma, who stitches shirt collars for high-end brands in a Bengaluru export factory, endure relentless pressure and abuse to meet impossible demands. Starting her day at 5:30 am, she faces verbal, physical, and sexual harassment throughout her shift. This graphic illustrates Rangamma’s exhausting routine, from early morning to midnight, highlighting the stress and exploitation she and her fellow workers experience. This systemic abuse has profound social and personal consequences.

Worker Story

Work Shouldn’t Be Torture. But When Yelling, Shouting & Physical Abuse Are Normalised at Garment Factories That Chase Targets, Workers Like Seetha Remain In Perpetual Fight-and-flight Mode

Desperately Seeking Respect

By Nikita Joseph

Three months into her first job as a tailor at a Bengaluru garment factory, 20-year-old Seetha (*name changed) had had enough. A small error she had made incited her supervisor to yell and throw a bundle of cloth at her, even as her colleagues watched. She tried her best to stay on but she only lasted another three months, before she resigned in the hope of finding a better workplace.

This was in 2007. More than 15 years on, the 36-year-old has concluded that her work environment is not going to change, no matter how many job hops she does. Seetha appeared for the interview tired, wary, and afraid of losing her job for talking about her experiences at four different factories in a decade.

“It is torture,” is how Seetha described her work environment. From skipping lunches and toilet breaks to staying mum through coercion and abuse from supervisors, she has seen it all, so her employers can meet unrealistic production targets that seem to be increasing every other year.

Why Is Work ‘Torture’?

Seetha’s is not an isolated experience. The Home And The World of Work report cites how in its survey of 184 Bengaluru garment workers , 100% and 61% of the local workers (those hailing from Karnataka) reported experiencing verbal and physical abuse (having a bundle of clothes thrown or a chair pushed at them) respectively. As many as 68% of the workers said that their factory imposed time restrictions on the use of the toilet, and these are enforced by controlling the number of visits and amount of time spent in the toilet, as well as through verbal abuse. Nearly 66% experienced physical isolation inflicted as a form of punishment and 39% had undergone sexual harassment.

These methods are imposed due to short lead times (time given by brands to contract manufacturers to deliver orders). There is intense pressure on shopfloors to complete work, and supervisors pass on the burden to workers through verbal, physical, and sometimes sexual abuse, and penalties. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) refers to these extractive labour practices as situations in which persons are coerced to work through the use of violence or intimidation (Read more).

Garment factories have been using such practices despite interventions and international outcry. Many of them have devised novel ways to extract more from their employees. At Seetha’s second workplace, the dining room was strategically placed four floors above the shopfloor so workers would rather miss lunch and not ‘waste’ time using the stairs. “The days I managed to drink water once a day were memorable,” she recalls.

The other tactic from the same employer was to force workers to do overtime (OT) regularly and give them a day off instead of the mandatory OT pay. This is illegal as workers should be paid double their wage rate for overtime work. Seetha says she prefers to earn more because the regular wage is low.

No Break

When such work practices lead to physical ill-health, the workers find it humiliating to avail of sick leave. “If you’re here just for time pass, you might as well sit at home,” says the supervisor when workers go with leave requests. Permission is a long-drawn-out process – approvals have to come from the supervisor, floor-in-charge, Production Manager, HR, and sometimes, General Manager. Complaints lead to more work and penalties.

Such practices have been normalised in the garment industry over the years. Among the respondents for the Home And The World Of Work (link) research study, about 82% of the local workers said that they did overtime work, while only 58% of them were paid double for overtime work. In addition, about 70% of the workers said that they are asked to work on Sundays or other public holidays, but 58% of them are given what is known as a compensatory off sometime during the week, instead of the legally mandated overtime pay.

At a point in her five-year tenure as a helper at factory number two, Seetha was fed up with being hauled up by her supervisor for every small ‘mistake’. In response, she garnered the strength to take an unexpected step. Once she countered her supervisor: “I’m doing my best to complete the work on time by not even eating lunch. If you can do what you are asking me to, I’ll admit that I’m at fault.” Such a response only elicited more retribution.

When things went beyond control, she reported her supervisor to Munnade Social Organisation, a Bengaluru-based non-profit dedicated to the welfare of women garment workers. The Production Manager was brought in and upon checking Seetha’s machine, he accepted that she was right. He dismissed the supervisor and took her back to work.

New Ways Of Control

Small victories like this remain exceptions, as strategies to systematise a culture of coercion continue. After the pandemic lockdowns, work pressures have intensified. The factory started appointing more female supervisors, touted under the garb of female empowerment. “Female supervisors can harass us more as they even follow us to the washrooms and lunch hall,” says Seetha. “They come inside the washrooms and accuse us of taking breaks.”

Seetha has witnessed how many former friends and peers have changed after being promoted to supervisors. “They don’t have the permission to remain friends and if they talk to some workers differently, they will be termed partial,” she says.

Seetha may not be surprised by these everyday betrayals, but she is not resigned to her fate. During the lockdowns, she engaged in piece-rate work from home for another factory, which did not pay two months’ dues. Seetha decided to change her factory and is now at a marginally better workplace. Here, the latest by which workers can enter the gates is 9:15 am, after which they have to report late coming, whereas, in factory number 2, the gates were shut by 9:05 am. She is also paid the legal rate for overtime work now. Her current role, which involves stitching collars, does not come under a target-based system. These are only small changes, but Seetha feels much more relaxed about work than before.

Salaries across all factories remain abysmally low and hardly rise beyond Rs. 9,500 per month. Seetha has chronic back pain, headache, joint pain, and anaemia. She is the sole breadwinner of her family, as her husband has stopped economically supporting them. The one time her face lights up is when talking about her son, whom she has admitted into a computer science course at a private college. She dreams of a bright future for him, where he is respected at his workplace and free from abuse. And perhaps then, she can finally let go of a career that has taken much more than what it has given her.