Ritu’s Journey from Bihar to Bengaluru’s Garment Lines Shows How Long Shifts Push Women to Consider Leaving the City for a Better Life

When Ritu* left Patna for Bengaluru in 1999, it was meant to be a brief stop. Her husband had found factory work in the city, and garments seemed to promise steady wages. More than two decades later, at 42, the city is still home to her. But for Ritu, it is a home stitched together with fatigue, resilience, and the constant struggle to balance survival with dignity. (*name changed)

“I wake up at 5 am, I work until 11 pm. There’s no time to rest,” she says. “If I feel sleepy, they tell me: ‘Don’t come if you don’t want to work’. But I have to work.”

Finding A Foothold in a New City

Ritu remembers her early years in the city as isolating. She didn’t speak Kannada, struggled to understand supervisors, and felt out of place. “If someone shouted at me, I couldn’t even answer back. I just stood quietly.”

Still, she stayed. “Bihar has no jobs. Here, at least, the factory paid the salary on time.” Off the factory floor, Ritu is surprisingly bubbly and quick to smile. Even in conversation about hard shifts, she has an easy laugh and an openness that puts people at ease.

Her husband, an auto driver, works long hours, often starting at 6 am. Together, they bring home about ₹20,000 a month. “It sounds like a lot,” she says, “but it disappears.” Rent is ₹6,000. Daycare for their three-year-old daughter is ₹2,500. Just milk for the child costs ₹2,000 a month. Managing these expenses is even harder because Ritu has lived with diabetes since her twenties and also struggles with a thyroid condition, which leaves her chronically tired.

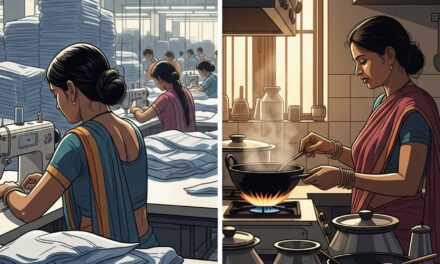

A Second Shift At Home

Once the factory shift ends at 5:30 pm, another begins. Dinner must be cooked, her child bathed and fed, the house kept in order. Her sister helps with childcare, but the weight of the household still falls on Ritu.

“When will I sleep? When will I cook? When will I look after my child?” she asks. On most nights, sleep comes only by 11 pm, leaving her with 5–6 hours before the cycle repeats. The long days take a toll: a past miscarriage and unrelenting fatigue have made her cautious about pushing her body too far.

When she does find a spare moment, Ritu reaches for her phone. She loves Hindi TV serials on YouTube and giggles that she’s “addicted,” a small, guilty pleasure in a life with almost no free time.

Even finding childcare has been fraught. “Once, I paid ₹2,500 to a neighbor who kept kids in a bathroom. No safety. But what could I do? I had to go to work.” Today she uses a paid daycare, one she trusts because it’s clean and has proper toilets. “They give the children milk. At least there, I don’t worry so much.” Whether out of unawareness or distrust, she does not depend on her factory to provide childcare, which is a mandatory provision under the Factories’ Act*.

Pressure On The Line

Her work is never light. As a stitching operator, she is often made to take on far more than others. Instead of recognition, experience brings her heavier workloads and arbitrary transfers. “Sometimes they shift me randomly from one section to another,’’ she says. When she was deputed to packaging, Ritu was given 12 different tasks because she is an old hand. ‘’There is no respect.”

Pregnancy made her even more vulnerable at work. “When I got pregnant, the factory told me to resign,” she recalls. She left as instructed, but the management withheld 15 days of her wages, leaving her with neither income nor maternity protection.

The law may say eight-hour shifts, but Ritu knows how easily rules are bent. “At the factory, they made me do overtime every day. Now they want to make shifts of 10 hours, plus 2 hours overtime? I can’t do it. I have a baby. I cook, clean, and work. My health will break down.” Cividep’s 2024 report The Home and the World of Work found that migrant women workers face language barriers, isolation, and stricter living conditions — pressures that make longer hours even harder to endure. (Read here: The Home and the World of Work)

Ritu’s story is not unique. Many women workers face excessive workloads, frequent shifts across sections, and little recognition, even when experienced. While the Maternity Benefit (Amendment) Act, 2017 legally protects pregnant workers with paid leave and job security, enforcement is weak, and overtime rules are routinely bypassed. These systemic gaps, particularly around overtime, put women under immense physical and mental strain, making daily work unsafe and unsustainable.

Even Machines Heat Up

Ritu’s refrain is sharp and clear: “I am not a machine. Even machines heat up.”

Her words are not just about her own exhaustion, they point to a larger reality built into the way garment work and women’s lives are structured. For women like her, the factory does not recognize the second shift of unpaid domestic labour. According to The Home and the World of Work report, garment workers spend about six additional hours each day on household chores, and nearly 70% said the combined burden of factory and home was “extremely tiring.” Longer hours at work mean less care at home, poorer health, and children left without attention.

“We will just go back to Bihar and eat roti with salt if we have to,” she says firmly. “But we won’t destroy our health.”

What Keeps Her Going

Despite her hardships, Ritu carries hope in her daughter’s future. “I want her to study. If she can finish school and get a better job, then all this will be worth it.”

She also feels stronger than before, less afraid to speak up. “Earlier, we didn’t know who fought for us. We feared outsiders but now, we understand. Now, we speak up. We know someone is listening.”

For her, sharing her story is itself an act of resistance. “Now I feel stronger. I know people are there for me.”

Ritu at a Glance

- Age: 42

- From: Patna, Bihar & in Bengaluru since 1999

- Family: Husband, 3-year-old daughter, sister

- Work: Garment-factory stitching operator

- Household Income: ~₹20,000/month

- Key Expenses: Rent ₹6,000 • Daycare ₹2,500 • Milk ₹2,000

- Daily Routine: Up 5 am, factory 9 am–5:30 pm, home chores till 11 pm

- Health: Diabetes, thyroid issues, chronic fatigue

Dream: “I want my daughter to study and get a better job”

NO TIME TO SPARE SERIES

Karnataka’s proposal to extend the workday to 10 hours under the Shops and Commercial Establishments Act has sparked debate, largely focused on IT and ITeS employees. But for garment workers, especially women, the reality of longer hours began quietly after the 2023 amendment to the Factories Act, which increased shift lengths and enabled night work. Now, with changes likely to affect smaller, often informal garment units as well, the risk of overwork and exploitation deepens. ‘No Time To Spare’ is a series of ground reports that draws from Cividep’s ongoing fieldwork and research, including our recent report and documentary, to bring worker well-being into focus. Each piece captures one voice, one story, from the margins of Karnataka’s garment industry.