Pradeepan Ravi Explains Why Brands Should Adopt International Standards Post-Covid. This Analysis Forms Part Of the latest research on working conditions That Pradeepan Co-Authored with Sreyan Chatterjee

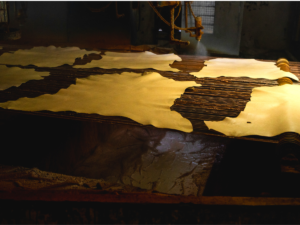

Kumar, a 51-year-old tannery worker in south India, has been struggling to make ends meet after the COVID-19 pandemic hit the leather and footwear industry hard in 2020. “We are not getting regular work. I am scared to take a day off as my supervisor will deny me work for the next three days. I have exhausted the little savings I had and have accumulated a lot of debt now,” Kumar says.

But the worst bit is that he doesn’t know when the situation will improve. Despite the industry showing positive growth in 2021, workers like Kumar have not seen any improvement in their conditions. Their lives were already challenging due to poverty-level wages, precarious work, gender pay gap, and lack of effective grievance mechanisms and freedom of association, according to a recent study jointly authored by Pradeepan Ravi and Sreyan Chatterjee of Cividep. “My son has also lost his job. The salary I draw is not enough to feed the family,” Kumar says.

Wages Below Legal Minimum

Poor wages are a widespread issue across the sector, with one-third of tannery workers and more than half of shoe factory workers surveyed receiving wages below the legal minimum (INR 9,103)* for the sector. Further, the majority of respondents said their wages were not enough to meet their basic needs. In shoe factories, where female workers outnumber males, they often receive significantly lower wages than their male counterparts.

Access to paid leaves is a rarity for workers in the leather and footwear sector. The study found that paid leaves were denied to temporary workers, and even for permanent workers, the process to avail of such leaves was tedious and often involved abuse and harassment.

“I joined the company six months ago as a helper in the upper division. This is my first job. I had to start working because my husband lost his job in a tannery during the COVID-19 lockdown period. I have to work all 30 days a month to earn INR 6,000 to 6,500 [about $80 to $90]. As a temporary worker, I am paid only for the days I go to work, ” says Amudha, a 21-year-old shoe factory worker.

Despite working without taking leave, Amudha’s wage is not sufficient. “I am pregnant now, and I will have to leave the job in another six months. I do not know how we will manage the household expenses as my husband is also not working,” she says.

Missing Entitlements

Temporary workers make up a significant portion of the workforce in shoe factories around Ambur in Tamil Nadu. They help the factories meet tight production deadlines during peak seasons, but are not treated equally to permanent workers. None of the temporary workers surveyed were provided with social security benefits, and they were denied paid leaves.

Female workers on temporary contracts were also not eligible for maternity benefits. Workers like Amudha, who are first-generation industrial workers, hope for a better life but the industry only pays them enough to survive.

Where Is The Space To Talk?

The lack of effective grievance mechanisms and freedom of association exacerbates the challenges faced by workers in the leather and footwear sector. Many workers are not aware of their rights or are too scared to speak up about the abuse and exploitation they face.

“There are no unions in my company. The management will fire me if they get to know that I get in touch with any union outside. However, we have a committee in our company and 3 rupees [EUR 0.03] is deducted from my wages for this. But I do not know much about it,” says Jamila, a female shoe factory worker, aged 36. For any issues within the company, she is at the mercy of her supervisors.

Way Forward

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the fault lines in the supply chain. The losses faced by international brands and retailers that source leather and leather products from the region were passed on to the workers. Now, despite the industry getting back on track, there are hardly any efforts from the brands to address the precarious conditions of workers.

Social audits that often fail to capture the perspectives of workers and their representatives are not the answer. Instead, the brands should carry out human rights due diligence in line with international standards to map the risks in their supply chains and address them.

It is also important that social dialogue and stakeholder engagement are embedded in such processes to ensure that the workers’ voices are heard and respected. Consulting local civil society organisations on key issues of workers and industry, and reaching out to workers’ representatives can be a starting point for such a process. Purchasing practices, including the price that the brands and retailers pay to the suppliers and the lead time given to them, influence the working conditions in the factories. Hence, the brands should ensure that the prices that they pay enable the suppliers to ensure living wages, and safe and secure workplaces for all workers.

Study Recommends:

* Living wages for all workers

* Transparency & human rights due diligence in accordance with OECD guidelines for multinational enterprises

* Social security benefits, paid leaves to all

* Freedom of association

* Effective grievance mechanisms

* The minimum wage for unskilled workers in shoe factories is INR 9,103 (EUR 105) and INR 8,229 (EUR 95) per month. These figures are for the month of September 2021 when the survey was carried out.

(The survey was conducted in September and October 2021 with a sample of workers from shoe factories and tanneries in Ambur which predominantly cater to the export markets in Europe. A small number of workers from unregistered workshops and tanneries also participated in the study. The study was carried out under the Together for Decent Leather project supported by the European Commission. )