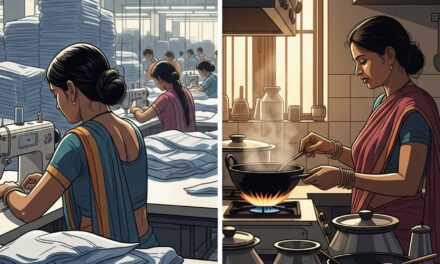

Like most others, the readymade garment industry too was battered by the lockdown announced in March 2020. A 2021 study reported that over half of the sector’s strong workforce was impacted by ‘forced resignations.’ Factories reeling under reduced demand and canceled orders, withheld settlements if workers refused to resign, canceled bus services, promised conditional re-employment, and so on.

The result was an influx of workers back to their native places, being unable to survive without their meager incomes. To gauge the severity of the crisis, Cividep along with Cardiff University, conducted a survey of over 400 workers in April and May 2020. 2

The vast majority lived in rented accommodations, and 96 percent reported their inability to pay for rent and essentials. Despite government orders requiring factories to pay until March, only 30 percent of workers reported receiving part-salaries while 10 percent received nothing. In subsequent months, many more reported non-payment of wages post the first lockdown. Even when some factories reopened from May, they could absorb only up to 70 percent of their workforces and pay for the number of workdays, which was 12 to 16 days a month.

Cividep’s Relief project: May 2020 to June 2021

These increasingly dire circumstances proved the need for some form of immediate relief and rehabilitation. Cividep began a rapid-response relief project for garment workers, with the initial allocation of ration and hygiene kits (packets of soaps and masks, along with sanitary pads for women and adolescent girls) with the support of FEMNET and Greenpeace. Later on, with the aid of Azim Premji Philanthropic Initiatives (APPI), Cividep also started disbursement of cash transfers of – rupees 3,000 each, for workers whose factories had shut down or were employed for only 12 to 16 days in a month, either as piece-rate workers or regular workers.

For enabling workers to avail this support, Cividep set up an online application form on its website. They were required to fill in their basic information, details about their needs and problems, and upload scanned copies of identity/employment documents. Our field partners helped in extending outreach and awareness among the worker leaders, factory committees, and the worker community about the project. They also trained field volunteers to help workers navigate the application process and upload the necessary documents. The verification team, comprising Cividep team members and volunteers, reached out to every individual applicant using the contact information provided and followed a rigorous process to explore various factors determining vulnerability. Whenever the phone numbers did not work (the case for almost one-third of applicants, due to factors like a lack of prepaid balance, or when the worker left Bangalore), the team reached out to factories and other workers to find alternative contacts. The team prioritized those who had experienced bereavement and had less familial support. These included single women, women-headed households, widows, and workers with elderly, diseased, and/or disabled dependents. Once verified, the transfer was made directly into the worker’s bank account.

From phone conversations, Cividep learned more about the exceptional difficulties workers faced. Almost every worker approved for support reported food scarcity, being unable to pay house rent or fees for their children’s schooling for several months. The health risks posed by the pandemic also resulted in many being advised isolation, or to seek medication and healthcare by themselves. In these circumstances, the cash transfers, though limited, came as a welcome relief for the 3,038 families that Cividep could reach out to. They hailed from garment clusters of Mysore Road, Peenya Industrial area, Kamakshipalya, Magadi Road area, Nelagadaranahalli, Gurguntepalya, Devanahalli, HS Cross, and Yelahanka in Bengaluru District, Tumkur district (urban and rural), Chikkaballapur, Mandya, Gulbarga, and Ramanagara Districts.

Some of their testimonials mentioned thus,

“I work in a factory and run the family alone. My husband and daughter died a few years ago and I am looking after my daughter’s children. The factory closed in March and opened only in June. I was paid only for 15 days in March. I could not pay house rent and the landlord wanted me to vacate. The money helped me to pay a month’s rent and prevent our eviction.” …………………………………

“I have worked as a tailor in a factory for the past three years. My sister died and her husband left their child with me. My parents and my own child are with me. My husband abandoned us after being unable to repay some loans. My factory closed during the lockdown and opened later. It was difficult to make ends meet. The monetary support came at the right time. I could support one child’s education by providing books.”

Looking ahead

The nature of outsourcing in global supply chains is such that there is a huge disparity between international brands and local suppliers in terms of power, wealth, and vulnerability to risk. Brands frequently drop ties with a supplier whose costs are rising or production efficiency is declining. This implies that factories operating on risky terrain with minor profit margins impose cost-cutting measures such as low wages, bad working conditions, and layoffs on their workers. The pandemic was no exception to this phenomenon and has highlighted more than ever, the need for ethical structures in the industry. According to estimates by Clean Clothes Campaign, the wage gap for Bangalore’s garment workers alone, from June to September 2020 amounted to US$ 20.9 million. 3 An important step by which brands can take responsibility in this crisis, is by delivering on their commitments to suppliers instead of canceling orders abruptly. Further, joint support systems can be initiated by consumers, retailers, and brands to aid pandemic-affected workers and enable their access to vaccination. Moreover, brands can use the lessons from the pandemic to collaborate with stakeholders in the supply chain for wage assurance and implementing costing models that ensure decent living and working conditions of workers, in accordance with the core labour standards of the International Labour Organisation.

References

- Shivanand, S., & Pratibha, R. (2021, March). Forced Resignations, Stealthy Closures: A study of losses faced by garment workers in Bengaluru during the pandemic. Alternative Law Forum. https://altlawforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/English_GATWU_ALF_Forced-resignations.pdf

- Jenkins, J. (2020, October 20). COVID-19 lockdown and the needs of garment workers in Bangalore, India. https://blogs.cardiff.ac.uk/business-school/2020/10/20/covid-19-lockdown-and-the-needs-of-garment-workers-in-bangalore-india/

- Neale, M., & Bienias, A. (2021). Still Un(der)paid: How the garment industry failed to pay its workers during the pandemic. Clean Clothes Campaign. https://cleanclothes.org/file-repository/ccc-still-underpaid-report-2021-web-def.pdf/view